The carrying costs of a home aren’t just those that maintain the house itself, but those that also maintain the community—in other words, property taxes.

Property taxes are assessed based on home value and administered through a variety of local, county or state laws, so there’s no one exemption or loophole to use. However, the data does show a consistent trend across the country.

“(Rising property taxes have been from) home price appreciation, mostly,” says Hepp. “Home prices are up cumulatively some 40% to 50% since the onset of the pandemic, so in a five-year period, we’ve basically seen home prices go up by 50%. So when it comes time for reassessment, folks are getting much higher tax bills.”

Hepp goes on to explain that rising taxes for existing homeowners are directly correlated to the affordability barriers for first-time homebuyers.

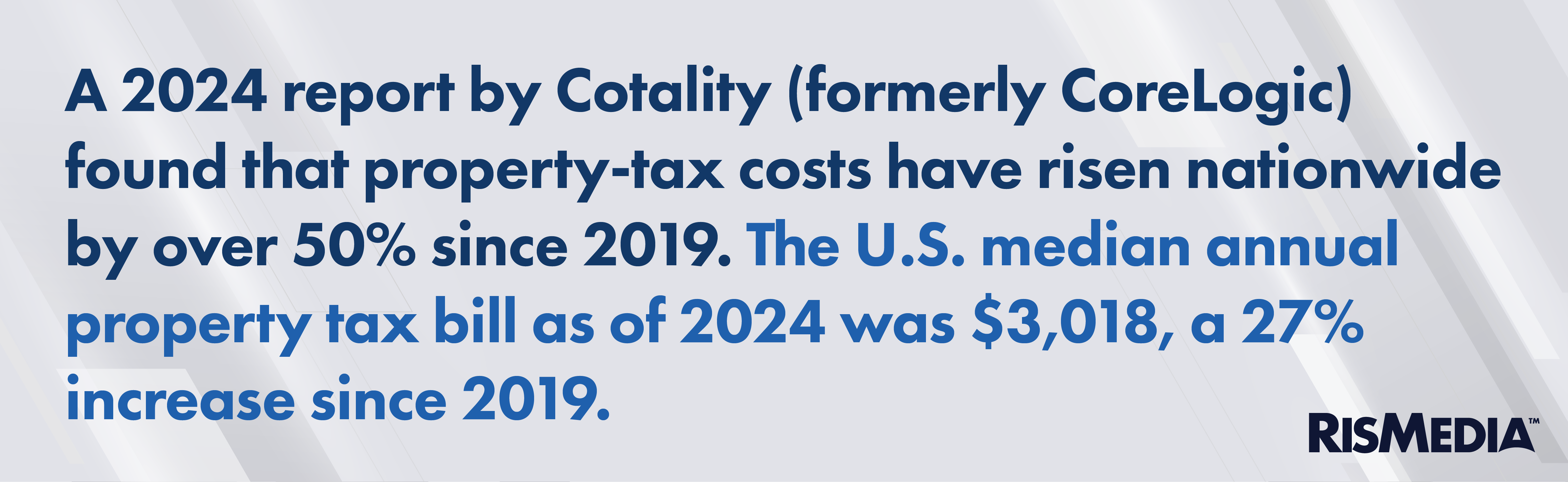

Cotality’s 2024 report found that property-tax costs have risen nationwide by over 50% since 2019. The U.S. median annual property tax bill as of 2024 was $3,018, a 27% increase since 2019, citing what Hepp calls the “mixed blessing” of high home prices.

“We’ve never really seen a period where home prices went up that much and remained at a level, as I mentioned, going into the great financial crisis. Home prices went up about similar amounts, but then declined, reset almost completely in a period…from 2006 to 2009,” she says.

Per Cotality, the state that saw the highest increase in property taxes during this time period was Colorado. In 2024, the Centennial State’s median property tax was $2,568, a 52.9% increase since 2019. This was followed by Georgia (a 51.5% increase to $2,186) and Florida (a 47.5% increase to $3,101).

Nguyen offers an on-the-ground perspective on this tax rise.

“Last year, in a majority of the counties (in Colorado), property taxes almost nearly doubled,” she says. “Existing homebuyers who have purchased could afford the home at the time, but now their taxes have made their mortgage payment unaffordable. I’m beginning to have a lot more conversations about the increase in insurance, but a lot of people don’t know this going in, so (it’s) important for us to educate our buyers.”

Mattar also says that clarification with buyers is important; property taxes are one area where buyers know and expect costs going into the process.

“Any portal that you look at online, the taxes are right there on the listing,” he notes. “The only situations where it can be a little bit of a gray area are if the current owner of the home has multiple tax exemptions and/or a senior freeze. In those instances, the taxes reported on the listing are artificially low based on what they will be compared to what they will be when a new buyer purchases the property,” he says, noting that in such cases, it’s important to educate clients as to why the taxes are low so they understand that their tax bill might not come with the same exemptions.

As for newly constructed homes, where taxes can’t be assessed, “you kind of have to reverse engineer,” he says.

“Working with our attorneys, (we try to) figure out the range in which we think the taxes will likely fall based on purchase price and comps in the area,” says Mattar. “Outside of those, if we’re dealing with a very straightforward resale property, the taxes are kind of abundantly clear from the time we’re going to do a showing.”

Rising taxes have also brought changes to the tax proration calculation, Mattar says, because setting an amount ahead of time can backfire on your clients.

“When I first got into the industry 10, 11 years ago, we typically always put a tax proration into the contract. In terms of what our offer was, it was either 105% tax proration for the previous year or 110% tax proration for the previous year,” explains Mattar. “We’ve seen enough fluctuation in the property taxes where it’s become commonplace for a lot of agents, myself included, to put TBD in the tax proration section of the contract because each specific property may be in a different position where it was just reassessed and the taxes are going up way more than 5%.”

Asked about how states and/or local governments are reacting to property tax increases—and what resources are available for homeowners—Nguyen cited the “Tabor bill,” which, since passing in 1992, has prohibited Colorado from instituting tax increases without voter approval, and requires excess revenue to be refunded to taxpayers.

Voters in other states have been faced with voting on property tax remedies, and chosen different results. Georgia (which, again, has some of the highest property tax increases after Colorado) held a ballot measure called Amendment 1 during the 2024 election. Passed with 62% of the vote, this amendment introduced the “Homestead Property Tax exemption,” which acts to limit how much of a home’s increasing value can be taxed. (Counties are able to opt out of the exemption under the amendment.)

On the other hand, North Dakota proposed a measure that would have more or less eliminated property taxes in the state altogether. Despite taxes still rising in the state, voters overwhelmingly rejected this proposal.

Now, for liability reasons, it’s generally considered a bad idea to give a client specific tax advice—referring them to an accountant or a lawyer is the better call. That said, experts agree that as these costs stay in place, client education is key.

“(Property taxes and insurance costs are) now becoming an increasingly more important component of that affordability calculation, and people are paying more attention to it,” says Hepp, “so I imagine that going forward, potential buyers will be thinking, can I offer this if this property tax goes up?”