In a recent op-ed, Compass CEO Robert Reffkin compared NAR and MLSs to the NCAA in a strange analogy that dragged real estate into the world of college sports and NIL fights.

It’s a weird comparison, and it’s not the first time he’s floated an odd idea to stir things up. The problem with floating ideas like this is they don’t just highlight Compass’ nonsense, they make the whole industry look out of touch to the people we serve.

And that’s not a good thing in an industry that more than ever struggles to win consumer trust.

Agents are not the product

Let’s start with the basics. NCAA athletes were the product; they put their bodies on the line while schools raked in billions. These athletes had no other path, no freedom to monetize their own names or likenesses.

Conversely, real estate agents are NOT the product. The home is. I mean, that’s a pretty important distinction. Agents are hired to market and sell something they do not own.

Agents are already getting paid

This might be the most critical point. Agents already get paid.

A lot.

On a $400,000 home, the gross commission income is about $15,000 to the brokerage, which is then split with the agent.

That split is not a surprise. It’s negotiated upfront, and agents know the terms before they ever take on a client. This industry is very familiar with how to structure compensation for its services.

That is real compensation for the work provided. Comparing it to the NCAA model ignores this basic reality.

The “agent content” argument is shaky

In his piece, Reffkin leaned on the idea of “agent content.” Let’s be clear: photos, videos, and descriptions exist because a seller hired an agent to create them. They are not conjured out of thin air.

Ownership of that content is a red herring. The only reason this content exists is to serve the consumer’s interest in selling their property. To treat it as anything else, some separate asset to be claimed by Compass or anyone else, misses the point and works against the consumer’s interest.

By framing the content as about agent rights instead of consumer outcomes, Compass takes something built to benefit sellers and tries to reframe it as leverage for the brokerage. That narrative ignores reality and leaves the consumer out of the picture.

MLSs: local monopolies, and that’s OK

Are MLSs monopolies? At the local level, sure, they function that way. But not all monopolies are bad. Antitrust law has the “essential facilities doctrine,” which basically says it’s fine to be a monopoly if you provide an essential service and do it reasonably.

And to me, the MLS is as essential to real estate as water is to a city. It’s the utility that makes the whole market function. So what are we really talking about here? Does Compass want competition for every municipal water company too?

There are about 520 MLSs across the country, each independent and member-run. Taken together, the system is a patchwork of organizations all trying to do the same thing.

Functionally however, that creates inefficiency.

Brokers working across markets have to navigate new rules, systems, and fees every time they cross a boundary. For a national brokerage like Compass, that frustration is real. I share it too. The structure is fragmented and clunky, and in 2025 there’s no excuse for it to still be this way.

But again, inefficiency is not exploitation. MLSs weren’t imposed on brokers; brokers built them to give sellers maximum exposure and buyers the clearest view of the market. Compass benefits from that open access every day. Yet when the rules don’t line up with Compass’ positioning, suddenly the MLS is the villain. Funny how that works.

What’s missing? The consumer.

The strangest part of Reffkin’s op-ed is what he leaves out.

Buyers and sellers don’t really get mentioned.

We have to assume that omission was intentional, and it is telling. Consumers are already asking hard questions and testing the answers, and they’re using AI to get direct answers to their questions.

This is not just the new reality for real estate, it’s the new reality for EVERY industry.

For ‘funsies,’ I tested what Chat GPT would say if I asked it a question about my home sale, as if I was a regular consumer. Here are the EXACT prompts I used, and the response I received:

Prompt used:

Tell me directly, no bullshit: For me as a normal seller, is the 3-phased marketing plan better than selling my home on the open market. I just want to sell my house as fast as I can, and get the best price for it.

Here’s what ChatGPT responded with:

“Straight answer, no fluff: For a normal seller like you, a ‘3-phased marketing plan’ is not better than just putting your house on the open market right away.

Speed: If you want to sell fast, every day not on the MLS is wasted exposure. A phased rollout often delays that.

Price: The best chance to get top dollar is in the first 1–2 weeks on the open market, when buyer demand is hottest. If you stretch things out with teasers and phases, you risk burning that momentum.

Reality: What actually sells homes quickly at a strong price is:

• A competitive list price from day one

• Good photos and staging

• Maximum exposure (MLS + portals + outreach to agents)”

That is the kind of blunt answer sellers are getting today. No filters, no “3-phased” marketing gloss.

So when Compass promotes a “phased” strategy as innovation, while AI tools are telling sellers it wastes time and risks price erosion, the damage doesn’t just land on Compass.

It lands on the entire industry.

It makes us ALL look like we are playing games with consumers, even when most of us aren’t.

The real risk: trust

This is the bigger issue. Too often, the industry treats Compass’ outbursts as if they’re one-offs.

They aren’t. They’re a pattern.

Competitors and insiders may roll their eyes or ignore them, but consumers don’t see it that way. They see a major brokerage making promises that don’t match reality. Then they turn to tools like ChatGPT to check the facts.

When the answers don’t line up, and as my example above shows they don’t, consumers don’t just question Compass. They start casting a skeptical eye on the whole industry.

What’s really at stake

The NCAA comparison isn’t just silly, it’s a distraction. It casts agents, who are already well compensated, as the victims while leaving consumers completely out of the picture.

And that’s the part that should bother us most.

Consumers are stretching to buy $400,000 homes on $70,000 salaries. They’re putting everything they have into a purchase that represents their hopes, dreams, and ambitions.

None of that has anything to do with juicing a brokerage’s bottom line.

To me, Compass’ stance has nothing to do with fairness or innovation – that’s just posturing and nonsense, it’s really Compass chasing profit.

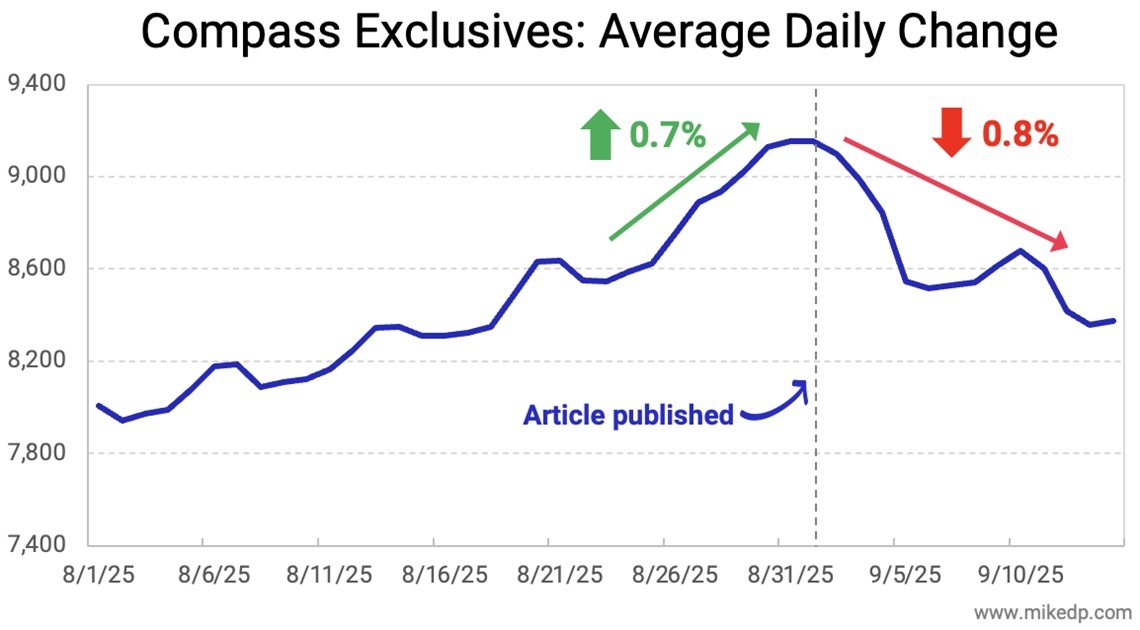

To illustrate the point, look at Mike DelPrete’s recent research. He showed Compass’ exclusive listings were climbing even as the company claimed Zillow’s ban was hurting its private listing business. That story collapsed the moment he published the numbers. Almost overnight, Compass reversed course and the exclusives dropped. Curious.

And that’s the pattern I’m worried about: spinning stories that at times defy logic and common sense, then shifting the narrative when the data is inconvenient. Each episode like this doesn’t just hurt Compass. It chips away at trust across the entire industry and makes us all look like we’re playing games with the very people we’re supposed to serve.