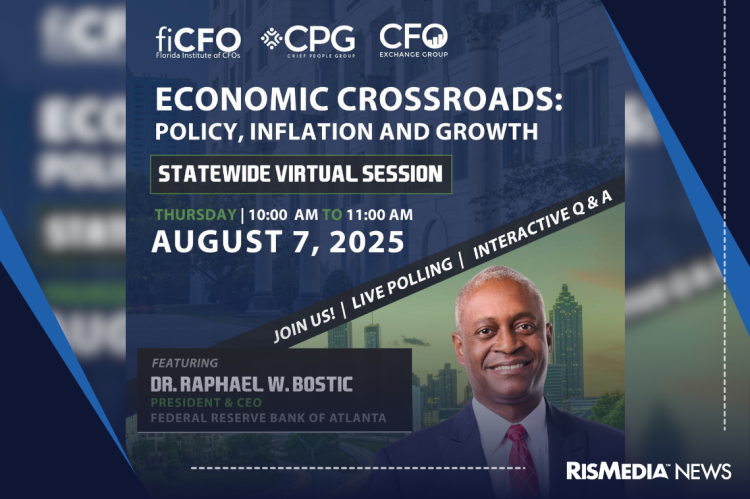

While mortgage rates have dropped to a four-month low without any interest rate cuts, Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta President and CEO Dr. Raphael W. Bostic said on August 7 that while job market risks have elevated, it remains premature to commit to cuts before the Fed’s September meeting, as key economic data is still forthcoming.

Speaking at a virtual event entitled Economic Crossroads: Policy, Inflation and Growth, and hosted by the Florida Institute of CFOs, Bostic emphasized the uncertainty in the current economic environment and the need for adaptability in policy-making. He shared insights on how businesses are navigating challenges related to tariffs and investment plans, highlighting the cautious approach many are taking. He also touched on consumer behavior, financial market resilience and the importance of Fed independence.

“Uncertainty has been perhaps the most frequently used word in 2025,” he said. “There have just been so many things that have gone on that have made it difficult to know exactly what’s going to be next. I do think that there is likely to be upward pressure on prices in the next six to 12 months. A lot of this has to do with the trade policy changes that are going on, but that puts real pressure on us.”

Bostic is not currently a voting member of the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC), which decides on raising or lowering interest rates eight times a year. He will be a voting alternate in 2026.

The Federal Reserve will meet on September 16 – 17 and is generally expected to lower its benchmark policy rate by 0.25 percentage points. The current rate has remained steady in the 4.25% to 4.50% range for the past five meetings.

A sharp drop in mortgage rates is likely at least partially the result of markets already pricing in a September rate cut, meaning there might not be another drop based on the FOMC vote next month.

Over the weekend, Michelle Bowman—a Fed governor who does currently vote on the FOMC—told an audience of bankers in Colorado that she believes the Fed should lower rates three times this year, meaning a cut at every scheduled meeting.

“I see the risk that a delay in taking action could result in a deterioration in labor market conditions and a further slowing in economic growth,” Bowman said, adding that she believes upticks in prices reflect “limited passthrough” from tariffs. Uncertainty, in Bowman’s view, largely stems from labor market conditions, and she broadly downplayed the effect of any tariff-related shock to the economy.

Bostic, on the other hand, noted the potential for lasting effects from tariffs.

“The question that I’ve been asking our team,” he said, “and asking myself is, does the economics textbook model fit today’s environment? There are reasons pretty compelling that suggest we should be somewhat skeptical about that. Whether tariffs are a one-time thing, or whether they’re going to be more persistent in their effects, and might even cause structural changes, is perhaps the most important question we have today. This has not been a one-time thing where you wake up one day and everybody knows what all the tariffs are.”

“Consumers will not respond to a continuously evolving environment,” he added. “That has caused a lot of businesses to just pause and say, ‘I’m not going to do anything until I know exactly what’s going on, where we stand in terms of our cost basis.’”

When it came to the labor market, Bostic expressed surprise at the recent data.

“The numbers last week really raised a question is as to whether we’re still at full employment or whether we’re moving away from it in a way that should mean that those risks, the risks that our two mandates (lowering inflation and unemployment) are much more imbalanced as opposed to it being inflation is a big risk and employment is not right now. The idea that the standard approaches to collecting data might not capture all the things that are going on is not a huge surprise.”

Bowman focused more on the labor market as an immediate risk to the economy in her remarks, calling the most recent report “consistent with greater risks” to the dual mandate.

“In my view, economic conditions appear to be shifting, and as a result, we should reflect this shift in our policy decisions,” she said.

Turning to the financial markets, Bostic acknowledged the complexity, saying that “the financial markets are not our mandate. Our mandate is employment and stable prices. So I spend much more time focused on that. I’m hopeful that we get through the elevated pricing pressures in an orderly and quick way so that we can actually start to return our policy rate to neutral. I think my outlook today is that we’re going to get there next year, probably to the middle to the later part of it, but there’s so much moving.”

Bostic explained that he has been reminded about how previous Fed Chair Alan Greenspan used to say that the country was winning the battle against inflation if no one was thinking about it.

“But this is kind of the flip side of that,” he noted. “It’s on the front page every day. So people are thinking about this, and I worry about what that means for how consumers and businesses will approach their strategies for engaging in the marketplace moving forward.”

Bostic’s conservative view on 2025 Fed rate cuts conflicts with that of JPMorgan, the nation’s largest bank, which anticipates the Fed will cut rates several times over the next four meetings. Previously, JPMorgan had predicted only one rate cut in December. The change in outlook is partly attributed to President Trump’s nomination of Stephen Miran, his chief economic advisor, to a temporary seat on the FOMC. Trump has insisted that rates be lowered but has met continual resistance from Fed Chair Jerome Powell.